Heiko Bleher completes his two-part review of this notorious fish by highlighting the Pygocentrus, Pygopristis and Pristobrycon genera.

The late Jacques Géry, who probably worked more on piranha than anyone else, sub-divided the Serrasalmus genus into Serrasalmus, Pygopristis, Pristobrycon, Pygocentrus and Taddyella and he felt the latter two were the true piranhas.

However, recent research has eliminated Taddyella — leaving Pygopristis, Pristobrycon and Pygocentrus.

There are 20 recorded Pygocentrus, but only three species are considered valid. Seven existing names should be valid and I have illustrated four additional forms which I captured and which are possibly undescribed.

Fourteen records exist of Pristobrycon, but only five are considered valid. I believe there’s one more. In Pygopristis there are six records with one valid name.

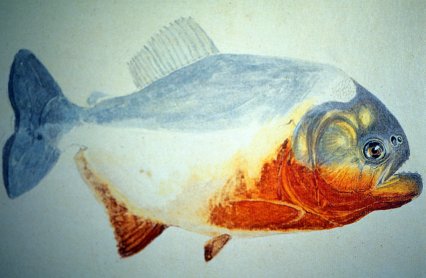

The Pygocentrus species comprise most of the so-called 'red-bellied' piranhas, but Jacques and I found out this species to actually be Pygocentrus altus Gill 1870,(above) from the Río Marañon, the middle and upper Amazon system.

Pygocentrus nattereri (above) has never been bred in captivity and hardly ever exported for the trade or public aquaria, as it is restricted to the Rio Guaporé, and Cuiabá. In 2011 I found in the upper Yavari, as well as earlier in the Rio Juruá upper Purus basins, red-bellied small piranha species, which may belong to the real P. nattereri or are an undescribed form.

Nattereri and altus are similar, but altus grows to 25-30 cm/10-12” TL while nattereri only reaches 15cm/6”. The P. altus tail has a bright black band from near its base spreading deep into the tail and a bright black seam edging the tail’s end. P. nattereri has an almost unseen thin black band in the tail’s base and a very narrow black seam at the tail’s end.

All populations of P. altus have two horizontal rows of black dots in the middle and in the upper part of the dorsal fin. Every altus population I have researched has this, except the one from the lower Purus basin which has a dusty colour pattern in its dorsal but no black dots. P. nattereri has no dots, nor any design in the dorsal fin.

P. altus has, during juvenile and semi-adult stages, a red ventral body, red pectoral, ventral and anal fins similar to P. nattereri, but this fades and disappears almost completely in older age, except for the pectoral and ventral fins. Red rarely remains in the anal fin.

More red-bellies

In aquaria the red belly disappears even earlier in age, most tank-bred P. altus losing their ventral colour at semi-adult stage and also in the fins. The entire body will normally turn an almost unified dusky-silvery, often darker dorsaly and lighter ventrally.

In P. nattereri all adults retain their bright red ventral colour patterns and all lower fins remain bright red throughout their lives.

However, those two are not the only 'red-bellied' Pygocentrus species. These also include P. notatus from Venezuela which is endemic to the Orinoco basin and wrongly considered a synonym of Serrasalmus cariba. Size difference and colour patterning differ here.

In the Orinoco basin P. notatus lives in mimcry with Piaractus brachypomus, another 'red-bellied. species but a vegetarian which belongs to the subfamily Myleinae. The picture shows Pygocentrus notatus, above, and Piaractus brachypomus, the vegetarian Pacu, below, in perfect mimicry in Venezuela. The latter is widespread, also in the Amazon basin, and often found with 'red-bellied' piranhas, even in the Guaporé-Marmore rivers sympatric with P. nattereri. P. brachypomus grow large and adults lose their ventral colour.

The other smaller piranha species having red bellies for life are my Pygocentrus sp. 1 'Guaporé' known only from the Rio GuaporeÌ: Pygocentrus sp. 2 'Paricatuba' which I’ve found several times in the Lago Paricatuba, lower Purus basin, Brazil, and Pygocentrus sp. 3 'Jari' which I collected in the Rio Jari, Boca do Lago Jari, in the Purus basin, Amazonas, Brazil. This latter fish has white dorsal and caudal fins, the latter with a small darker seam.

Distinctive head

No type is known of P. palometa and it appears no one has seen it alive since its description in 1850 from the lower Orinoco, Venezuela.

I consider P. ternetzi (Steindachner, 1908) pictred above a good species, although some place it in synonomy with P. nattereri. It is only known from the Rio Paraguay and Paraná basins to Argentina, has a distinctive head, not ventrally red, just a light orange-yellow and grows to 25cm/10” SL.

There’s a jet black, very large piranha which I caught in 1976 near Humaitá in the upper Madeira basin. It has the largest dorsal, anal and caudal fins I’ve seen in any piranha, being more than 40cm/16” long. It’s my unidentified species and should be placed to Pygocentrus. I have not seen it in aquaria since the 1970s.

The last Pygocentrus species, which Cuvier described in 1819 as Serrasalmo piraya, is from the São Francisco basin. It also grows large and also very different to the red-bellied piranhas.

Only five are considered valid in the genus Pristobrycon and I consider one more as P. aureus (below) is rarely shown correctly.

In 2004 I caught a very strange looking piranha. First it was identified as P. striolatus, but when Géry and I examined the specimens closer, and checked with the describers Spix and Agassiz, and their painting which matches the specimens collected, we realised its correct placement.

Another species Géry and I reinstated is Pygopristis antoni (Fernández-Yépez, 1965). It was described from the Río San José, Estado Guárico, in Venezuela. In 1972 Géry had already accepted it as a good species after some had considered it a synonym of Pygopristis denticulatus (Cuvier 1819). However, Géry made a detailed drawing and the specimens collected in the type locality matched the morphology of P. antoni, not P. denticulatus.

Colour changer

Pristobrycon calmoni from the lower Amazon is a beauty that doesn’t grow all that large and changes colours from baby to adult. It’s also said to occur in the Orinoco river basin, but I never found it there.

I have been collecting in the Rio Atabapo since the 1970s and brought back the first real Pterophyllum altum from there, but had never had Pristobrycon careospinus. I only have the original drawing and the holotype in pictures and don’t think it has been exported for the hobby.

Pristobrycon maculipinnis, is also from the upper Orinoco basin in Venezuela, but the adult schooling piranha I found in the Iriri in Brazil matches the decribed species.

Pristobrycon striolatus was described by Steindachner in 1908 from the lower Amazon, actually from the Rio Pará Orinoco river basins and said to be found in the northern and eastern Guiana Shield rivers: Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname and Venezuela. I collected them together with my Pristobrycon cf. calmoni near Terra Santa in Nhamundá lake.

One more Pristobrycon should be considered valid — that’s P. scapularis (Günther 1864) and still a synonym of Pristobrycon striolatus (Steindachner 1908).

The last species grouped with carnivorous piranha is the monotypic Pygopristis denticulata — the least evolved to predation. Young ones resemble tetras, with the body less deep than Pristobrycon, and its adipose and caudal fin is very large.

This species has weak suborbitals and jaw muscles. It does not have a spine after the anus, unlike the other piranhas.

Fact and fiction

Few fish have been given a tougher reputation than the piranha, but is fiction greater than fact?

Fiction says they are shoalers able to remove much flesh very quicky. That shoal is attracted by blood and noises of disturbance and a small group devouring prey is soon joined by another — and that a man with a bleeding wound will certainly be attacked.

The fact is that I was once snorkelling in the Guaporé at the Brazil-Bolivia border river and spotted in about 3m/10’ of water a beautiful large Echinodorus species. The moment I reached the plant the clear water turned dark and I saw a giant migration of black piranhas.

At least 10,000 started to circle me, cutting off any escape. This mass — all adults — swam around and over me, but suddenly swam on and disappeared as fast as they had arrived.

This was a giant breeding migration upriver and if humans really were their prey, they would have devoured me in seconds.

How to keep them

Décor should consist of white or beige sand, possible with leaves, driftwood and/or rocks where the fish can hide or escape to. It’s not easy to keep them with aquatic plants, but have floating plants and create some shade.

Even the smallest species should have an aquarium at least 80cm/ 32” long. For larger piranhas, such as Pygocentrus altus and Pristobrycon aureus the minimum should be 100cm/40”. Almost all of these genera live in groups so keep at least three of each.

Every piranha aquarium should have excellent filtration and periodic partial water changes — especially if food is left over. I suggest weekly changes of 20-30%. The water parameters for Pygopristis, Pristobrycon and Pygocentrus depend on the species, but most are used to almost neutral water conditions, from pH 6 to 7.5, conductivity 50 to 300 µS/cm, and temperature above 24°C/75°F — the best average being 27-28°C/81-82°F.

Some species may jump, so have a tank cover or screen.

As for tank mates, only add South American species the piranha knows and for only as long as you can guarantee the piranhas are fed daily.

When I had Pygocentrus, the most carnivorous of the species, I set up a 250cm/8’2” aquarium that had four P. altus with five freshwater stingrays, groups of Myleus and Metynnis species, some large Hypostomus and Pseudacanthicus.

With the lesser aggressive Pristobrycon species you can place more different species, but they should all be large!

Sizeable Crenicichla, Heros, Mesonauta species, a group of the so-called Pacus (Colossoma, Myleus, Mylesinus and Metynnis) and very large suckermouth catfishes are suitable.

You can practically place any partner with the monotypic genus Pygopristis, but always keep P. denticulata in groups.

How to feed them

All species of these genera are carnivorous and need to be fed accordingly. They won’t survive long on pellets or any other dry food, not even freeze-drieds. Do that and they will eat each other!

Feed them with most larger frozen foods, such as mussels, large brineshrimps, bloodworms, even beef heart, but they prefer fish in larger pieces at least once a week.

I would only feed them once a day as I have seen overfed and pretty immobile piranha. Don’t over feed, as in in nature they can often starve for weeks.

Meet the species

In Pygocentrus there are three recognised and four additional species to be recognised with existing names.

There are possibly four species, of which three are small 'red-bellied' piranhas — and one being an unusual jet black Pygocentrus.

Pygocentrus altus (pictured above as juvenile)

Gill 1870. Type locality: Río Marañon or Río Napo, upper Amazon system, Peru or Ecuador. Considered by some to be a synonym of Pygocentrus nattereri, Kner 1858, from the Rio Guaporé.

Pygocentrus nattereri

Kner 1858. Type locality: Cuiabá and Mato Grosso, Brazil. This is restricted to the upper Guaporé (type locality) in Brazil and Bolivia and possibly in the upper Yavari and Purus river basins.

Pygocentrus niger

(Jardine in Schomburgk 1841). Although no types are known Géry recognised it as valid but as Serrasalmus (1972, 1977) and Jardin’s painting leaves very little doubt of it being a good species compared to the specimens that I have collected.

Pygocentrus notatus (picture by H.-J. Mayland)

(Lütken 1875). Type locality: Caracas. Found only in the Orinoco basin, Venezuela, it is considered by some to be a synonym of S. cariba, but the latter and the former are certainly good species.

Pygocentrus palometa

Valenciennes in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1850. Type locality: Río Apuré, Río Guerico, Lower Río Orinoco, Venezuela. No types known, but listed as valid as Pygocentrus palometa, Valenciennes 1850, but as a nomen dubium.

Pygocentrus piraya

(Cuvier 1819). Distribution: Known only from the São Francisco River basin, Brazil.

Pygocentrus sp. 1 'Guaporé'

Type locality: Rio GuaporeÌ near Surpresa Mato Grosso Brazil-Bolivia. This small red-belly was recorded and painted by Natterer around 1830, but not described until today.

Pygocentrus sp. 2 'Paricatuba'

'Red-bellied' species. Type locality: Lago Paricatuba, lower Purus basin, Amazonas, Brazil.

Pygocentrus sp. 3 'Jari'

'Red-bellied' species. Type locality: Boca do Lago Jari, Purus basin, Amazonas, Brazil.

Pygocentrus sp. 10 'Humaita'

Type locality: Rio Madeira basin near HumaitaÌ, Rondonia/ Amazonas, Brazil.

P. ternetzi

Steindachner 1908. Type locality: Rio Paraguay at Descalvados, Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Some consider this as a synonym of Pygocentrus nattereri, Kner 1858, but it grows to a much larger size and has a very different head formation.

Five recognised and one additional species to be recognised with an existing name are contained in Pristobrycon:

Pristobrycon aureus

(Spix and Agassiz 1829). Type locality: Equatorial lakes and rivers of Brazil. Distribution: Lower portions of tributaries of lower Amazon River and Guyana rivers, Brazil and Guyana.

Pygopristis antoni (picture by FernandÃ)

Fernández-Yépez 1965. Type locality: Río San José, Estado Guárico, Venezuela. This is accepted as a good species by Géry (1972) but later placed by some in synonymy of Pygopristis denticulata (Cuvier 1819).

Pristobrycon calmoni (picture by H. Schultz)

(Steindachner 1908). Type locality: Rio Pará, Brazil. Distribution: Said to occur in the middle and lower Amazon basin, as well as in the Orinoco river basin; coastal rivers of Guyana: Brazil, Guyana and Venezuela.

Pristobrycon careospinus

Fink and Machado-Allison 1992. Type locality: El Loro lagoon, Río Atabapo, Estado Amazonas, Venezuela. Distribution: Atabapo river in Orinoco river basin: Venezuela.

Pristobrycon maculipinnis

Fink and Machado-Allison 1992. Type locality: Caño Doyotomoni, tributary of Río Pamoni, south of the confluence with Río Casiquiare, Venezuela, Holotype: Distribution: Blackwater areas in tributary of Casiquiare, tributary of Atabapo river, Venezuela.

Pristobrycon striolatus (pictured as juvenile by H. Schultz)

(Steindachner 1908). Type locality: Rio Pará, Brazil. Distribution: Amazon and Orinoco river basins and northern and eastern Guiana Shield rivers: Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname and Venezuela.

There’s one species in Pygopristis:

Pygopristis denticulata

Cuvier 1819). Locality unknown (Guyana). Distribution said to be in the Orinoco river basin, northern and eastern Guiana Shield rivers; tributaries of lower Amazon: Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname and Venezuela.

Check out part one of Heiko Bleher's definitive guide to Piranhas.

Why not take out a subscription to Practical Fishkeeping magazine? See our latest subscription offer.