You may be shocked to find that the most prominent invasive aquatic species in the UK are perhaps the most common "oxygenating" plants found in the industry. Joe Augier looks at the impacts some of our popular aquatic plants can have on the environment.

So the title may seem a bit Hollywood and over the top, but there is a serious side to this article.

I have been a fishkeeper since I was a child, I went to Sparsholt College to study aquatics; I've have kept a vast array of different aquariums over the years and have worked in numerous aquatics shops around the country.

It's only since I have given up the aquatic retail trade and started to study a degree in ecology that I have learnt the true impact that the hobby has on our environment.

It all came to me when I joined a volunteer group at the college I attend called SINNG or Student Invasive Non Native Group. The aim of this voluntary group is for students to go to places that have been impacted by invasive non-native species and survey the damage done by these species, and if possible reverse this damage.

Invasive species cost our economy approximately £1.7 billion per year to deal with and thanks to the work of local action groups around the country like SINNG, and acting according to Defra’s best practices, it is hoped that not only will it benefit the environment but also the economy.

In fact whilst writing this article there has been some remarkable headway in the control on invasive aquatic species. The government has announced that five species of non-native invasive aquatic plant have been banned from sale in the UK, including one of the stars of this article - Parrot's feather (pictured above). As of April 2014 retailers will no longer be allowed to sell these plants and failure to comply will result in fines up to £5000 and a possible six months in prison.

My first trip out with SINNG took me to Penrose Water Gardens near Truro, Cornwall to map and remove invasive aquatic plants in the garden’s numerous ponds. Penrose Water Gardens have been actively involved in the SINNG project and have been promoting the use of native pond plants for some time, but even with the help of SINNG it has proved hard to eradicate invasive non-native plants completely.

When we arrived there we mapped the area and started to assess the level of infestation and after mapping the first pond it occurred to me: "I am responsible for this". You see the plants we were identifying and aiming to remove were aquarium and pond plants - plants that I sold to people. Plants that I was not aware had the impact that they do on our native waterways.

It was at this point that I made a promise to myself, to try and raise awareness of these problem species and if not eliminate them from the industry then at least give you, the consumers, the knowledge that I should have been giving you all those years ago about how to correctly identify and dispose of these pest species.

The most prominent invasive species are perhaps the most common "oxygenating" plants found in the industry, Parrot's feather (Myriophyllum aquaticum) and "Elodea" species (Elodea canadensis, Elodea nuttalli). The problem that arises with these species is the confusion in correctly identifying them.

Elodea has become something of a blanket term for oxygenators as there are very similar species that are easily confused, which leads us to the problem of which ones are safe? Native species like Potamogeton and Callitriches are not only safe, but are great oxygenators that would not cause problems if they were to enter our native waters.

But be sure to avoid plants such as Lagarosiphon major and Egeria densa; in my experience these are what you will commonly find being sold for coldwater aquariums as well as ponds.

Parrot's feather too has some very similar counterparts that are far better alternatives to this prolific growing plant, plants such as Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum) pictured above, Mares tail (Hippuris vulgaris) or Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum).

So now let's talk about identification! The information on the species below is provided by kind permission of Defra.

Parrot's feather

Scientific name: Myriophyllum aquaticum

AKA: Brazilian Watermilfoil, Myriophyllum brasiliense, Myriophyllum

proserpinacoides

Native to: Central and South America

Habitat: Still or slowly flowing water

Emergent growth, blue-green colour and feather-like leaves make this a distinctive water plant. Present year round. Unlikely to be found in fast flowing water.

Aquatic perennial, grows in emergent and submerged form. Both forms are similar in appearance. Most often found in nutrient rich waters. Grown in water gardens in UK since 1878, first recorded in the wild in 1960. Initial spread by improper disposal of garden and aquarium plants. Still found in some garden centres, often under one of its pseudonyms. Spreads by vegetative fragmentation, no seeds are produced in the UK.

Causes flooding by blocking watercourses and drainage channels. Can rapidly dominate a water body displacing native species.

Parrot’s feather is listed under Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with respect to England, Wales and Scotland. As such, it is an offence to plant or otherwise allow this species to grow in the wild.

For details of legislation click here.

Key ID features

Emergent leaves are stiff, bright green and the most distinctive form. Submerged leaves are more fragile and, after death, decompose quickly.

Dies down in winter, can be found submerged throughout the year.

Emergent shoots appear in spring when the plant becomes moreconspicuous. Blue-green colour of leaves is useful for identification.

Flowers are present from May to August, but are inconspicuous.

Similar species

The emergent stems of Parrot’s feather distinguish it from native Water-milfoil species: Spiked water-milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) Alternate water-milfoil (Myriophyllum alterniflorum) and Whorled water-milfoil (Myriophyllum verticillatum) which are never emergent, although the native species can produce short emergent flower spikes.

Parrot’s feather is also rarely, if ever, found in fast flowing water, unlike some native water-milfoil species. Submerged Parrot’s feather is difficult to distinguish from these species and expert assistance may be required.

Other species that can be confused with Parrot's feather:

Canadian and Nuttall's waterweeds

Scientific name: Elodea species (pictured below)

Native to: North America

Habitat: Still or slow-flowing, shallow or deep water

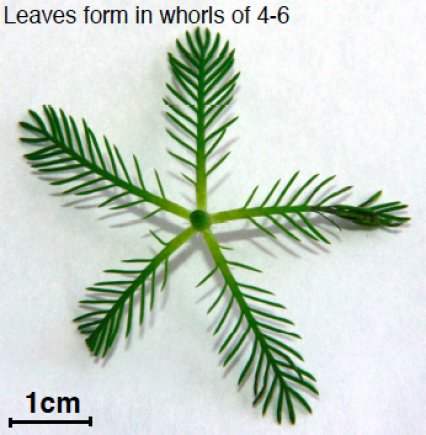

There are two non-native species of Elodea in the UK, Canadian waterweed Elodea canadensis and Nuttall’s waterweed Elodea nuttallii. Both are aquatic, submerged (apart from tiny white flowers borne on very long threadlike stalks just above the water surface) growing up to 3m in length, perennial and only reproduce vegetatively in the UK as all plants are female.

Nuttall’s waterweed is found in more nutrient-rich water than Canadian waterweed. First recorded as naturalised in Britain in 1966, it has since spread rapidly but is less common than Canadian waterweed in northern England, Scotland and Ireland.

Dense growth of these waterweeds in slow flowing rivers, drainage channels and canals can impede flow and exacerbate flooding. They replace native aquatic plant species and reduce biodiversity in lakes and ponds and interfere with recreational activities such as angling and boating.

Elodea species are listed under Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with respect to England and Wales. As such, it is an offence to plant or otherwise allow these species to grow in the wild.

For details of legislation click here.

Key ID features

Canadian waterweed and Nuttall’s waterweed are both perennial and are present throughout the year, though they can die back in winter. Tiny flowers are produced June to September.

Canadian waterweed is widespread and common throughout the UK. Nuttall’s waterweed occurs mainly in England.

Other species that can be confused with Elodea:

In Lagarosiphon major the lower leaves are spiralled at base, not in whorls; leaves to 3cm long. Flowers inconspicuous, with reddish petals.

You can download ID sheets on these and other invasive species on the Defra website.

How do invasive plants spread?

It is important that these species can be correctly identified so as to be able to avoid them in the future and perhaps more importantly, if you already have these species in your pond that you know how to dispose of them properly!

You see, one of the reasons why these plants so successfully invade and colonise new areas is that they are so robust. Something as simple as a bird landing in your pond and getting a tiny fragment of Parrots feather stuck to it has the potential to travel to another body of water and totally devastate the natural ecology of the new area it has invaded.

The same applies if you throw your excess plants down the drain, it will almost certainly take root somewhere further down the line.

In order to ensure that these plants don't contaminate any further places the safest thing is to remove as much from the pond as you can, leave it by the pond for 24 hours so all the bugs and critters can crawl back in, and then compost it (your garden plants will love it).

For further information about invasive non-native species visit the Defra website.

Why not take out a subscription to Practical Fishkeeping magazine? See our latest subscription offer.

Don't forget that PFK is now available to download on the iPad.