How far would you climb in order to breed? To the top of Everest maybe? One species of fish does the equivalent of just that. Nicolette Craig reports on this and other truly remarkable mountain-climbing gobies.

One of the highlights of the BBC television’s Life series last year was a magical sequence of a goby climbing a waterfall. The mountaineers shown were Sicyopterus stimpsoni, also known as the Nopoli rock-climbing goby or ‘O‘opu nopili and found in streams in Hawaii.

There are three species of waterfall climbing fish and one of shrimp in Hawaii and a number of others are scattered in places such as Iceland, New Zealand, Thailand, Venezuela, Japan and Puerto Rico.

The gobies in Hawaii are amphidromous, and spend part of their life in freshwater and part in saltwater. The adults live upstream in groups of up to 17. In breeding season the males are beautiful, having an iridescent brilliant blue colour and long blue and red dorsal fin undulating with the mood of the fish.

Females attach their eggs to rocks in streams where they are fertilised. Larvae hatching are washed downstream to the ocean to develop and this process takes some six months.

The juveniles then return to any freshwater stream and to pools upstream where they can live for several years.

To reach their adult habitat, however, they run the gauntlet of streams of predators — mostly native fish called sleepers — and must climb extremely high waterfalls. Yet the strength-sapping task of swimming and climbing the waterfalls takes just three days.

Climbing techniques

Different species use different methods to scale these falls. Dr Richard Blob, from Clemson University in South Carolina, and one of the world’s key researchers, told me: "All gobies have a sucker on their belly — even ones that don’t climb. However, the mouth of S. stimpsoni is also specialised, with the ‘lip’ of the upper jaw split to form a second sucker."

Facial change

Returning juvenile S. stimpsoni must wait before climbing any waterfalls as their skull undergoes a metamorphosis, the mouth shifting to under the body. This transformation takes less than two days and allows the previously omnivorous larvae to feed almost exclusively on algae from benthic substrates — and use their mouth to climb.

These gobies slowly climb the waterfall, alternately using mouth and pelvic suckers!

In contrast, Hawaii’s two other waterfall-climbing gobies, Lentipes concolor and Awaous guamensis, use bursts of rapid tail-beating and their pectoral fins. The difference in method is reflected in speed and those that use undulation advance some 30 times as fast as S. stimpsoni.

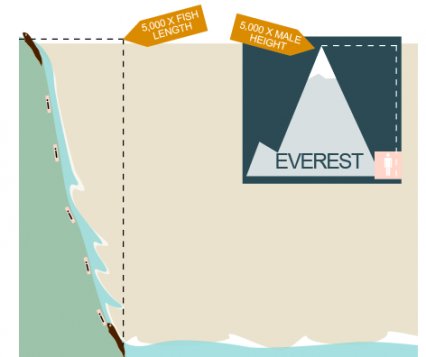

Everest effort

L. concolor is also more efficient, climbing waterfalls up to 350m/1,148’ high — more than 5,000 times its 7cm body length. This feat is unparalleled in the fish world and it’s the equivalent of a man of average height scaling Mount Everest!

Swimming and climbing may seem risky, especially when there’s no primitive homing instinct as seen in such as salmon.

Dr Blob added: "In selection trials only 70% of fish were able to climb a 2.4m/8’ artificial waterfall, which would suggest that 30% would not have reached adult locations to breed. However, the waterfalls in nature are much higher than 2.4m.

"We have estimated that at least 90% do not survive. This doesn’t even include the fish that hatch from eggs but either don’t make it to the ocean or die there before returning. The individuals that survive must be pretty tough!"

What reason could there be to make this journey? The answer may be two-fold. Firstly, the key predator of S. stimpsoni is the Sandwich island sleeper (Eleotris sandwicensis), another gobioid. These fish can’t climb waterfalls, so although a goby may have to swim through sleeper-infested waters, once over the waterfall it is pretty safe.

Studies have also shown the better goby climbers go higher upstream. This means that for any number of the native ‘O’opu, no matter how much their diet overlaps other species, they are rarely in direct competition with each other. This allows a number of similar species to live as ‘neighbours’.

Conservation

However, this is not a completely happy story. The extreme isolation of the Hawaiian islands mean that freshwater fish life is fairly impoverished, numbering only seven native species and less than 70 species in total.

Of the endemic species five are gobioid, all of which are amphidromous stream dwellers that have adapted to the rocky, steep, fast flowing nature of Hawaiian streams. This, together with the limited resource of freshwater, means they are extremely vulnerable to habitat destruction.

Robert T Nishimoto from the aquatic resources division of the Hawaiian government said: "The biggest threat to our native biota is loss of habitat. This includes stream dewatering for irrigation systems, channel modification, degradation of habitats and sediment load.

"We have been working on the Waipi’o Valley Stream Restoration Study to look at the ongoing restoration of one of Hawaii’s most threatened native ecosystems, freshwater and wetland stream habitats.

"This is one of very few stream restoration projects in Hawaii, but these may not be enough to significantly help.

"Alterations in flow to the natural streams have been said to decrease the size of eggs produced, the number of reproducing females and the overall breeding condition of those females.

"These fish also face threats from non-native species, such as suckermouth, long-fin armoured catfish and mosquito fish. There has also been a problem caused by people dumping their pet aquarium fish into local streams. Local papers report shoals of Convict cichlids around a road bridge."

Invasive polluters

Donald Heacock, aquatic biologist of the Hawaiian Department of Land and Natural Resources, added: "Invasive species are the worst kinds of pollution because they perpetuate themselves. They will out-compete or prey directly on native species.

"Suckermouth catfish eat algae in the tank and they keep eating it in a freshwater stream, competing for food with native shrimp, snails and fish. People dong this would be much better focussing on keeping their own native fish."

As more streams in Hawaii become affected by humans the amount of habitat that remains suitable for these gobies declines. Without these streams these amazing fish will no longer be able to complete their life cycle and ultimately this will lead to their extinction.

Take a look at the video below to see the abilities of rock-climbing gobies.