Keeping Otocinclus catfish in the aquarium

Dr Michael Hardman takes a look at Ottos - popular, fascinating but sadly often undervalued suckermouth catfish, that are actually great little algae eaters.

Whether you call them cascudinhos, ohrgitterwelse, ottos, dwarf suckermouths, algae scrapers or goblin plecs, catfishes of the genus Otocinclus are known the world over.

Most never reach more than an inch or two long (5-6cm) and they retail for just a few pounds each. They have delicate mouths and an appetite for soft algae, so are most often installed as mere cleaner teams in planted aquaria.

Yet has their reputation as gardeners kept them out of the parlour, always to remain in the servants’ quarters? I hope not, because we all know that good things come in small packages…

Otocinclus are found mainly in small to medium-sized streams with moderate flow. They are typically caught among marginal vegetation, especially in grasses and aquatic plants with lots of small leaves. They’re also taken in more open water, swimming in shoals of many thousands over sandy areas with submerged structures such as a snag of branches or leaf pack.

They occur from Colombia to northern Argentina and have only been collected east of the Andes. Some species have restricted ranges in Peru, Brazil and Paraguay, while others occur throughout the headwater tributaries of the Amazon and Orinoco basins.

Morphology

Their skeletons have ridges, flanges and shelves that tell us they have all descended from a common ancestor.

Otocinclus also have an air-filled sac that balloons off their oesophagus and helps them ride high in the water column — most armoured catfishes sink because they are so bony — hear better and it can also be a primitive lung when oxygen levels are low.

We know of 17 species of Otocinclus, or 16 if, according to some ichthyologists, O. affinis is placed in Macrotocinclus. Telling them apart is difficult in the aquarium, but you can get some idea by looking at the eye and tail, as eyes in Otocinclus come with and without an iris diverticulum.

This is a small flap that expands or contracts to regulate the amount of light let through the iris and what gives most suckermouth plecs their crescent-shaped eyes.

Most Otocinclus from southern and eastern Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina (O. affinis O. flexilis, O. mimulus and O. xakriaba) and species from the rios Tocantins (O. hasemani) and Araguaia (O. tapirape) have iris flaps.

Tell-tail signs

Tail patterns are also helpful when telling Otocinclus apart. Two species from Peru and Colombia (O. batmani and the Zebra otocinclus, O. cocama) have a thick and solid W-shaped blotch on the back half of the tail.

The Zebra otocinclus (pictured above) is the most beautiful and most expensive, but its care and behaviour is nevertheless typical.

At one time or another, most Otocinclus have been imported for the trade, but two species dominate the flow and are most commonly available at your shop.

O. vittatus has the widest distribution of any Otocinclus and is the main species exported from Brazil. O. macrospilus is an Amazonian species and a mainstay of Peruvian shipments.

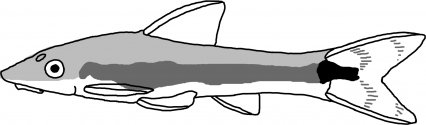

If you don’t know where they are from, look at their tails and caudal peduncles. In O. vittatus the thick dark stripe running along the middle of the body bulges at the start of the tail and narrows abruptly.

In O. macrospilus (above) the same stripe stops or becomes pale before the tail blotch, which can look like a fat spindle or diamond as it crosses into the tail proper.

In the 1980s and 1990s, two southern species (O. affinis and O. flexilis) were imported into the UK.

These can easily be identified on the basis of both having iris flaps and O. affinis is lightly pigmented with a thin stripe running along the back two-thirds. O. flexilis is more boldly patterned with green-gold blotches on a tan background.

Although most Otocinclus are sold or mis-identified as O. affinis (above) this species is now rarely seen, possibly due to habitat loss and land-use changes in its native south-eastern Brazil.

Home comforts

Regardless of species, all Otocinclus need the same care. It’s partly because their small size that they suffer in dirty water.

This is one reason why they thrive in planted aquaria with low stocking densities and immaculate water quality.

You’ll need powerful, mature filters capable of processing the aquarium volume at least three times an hour. Aim for no measurable ammonia or nitrite and low to no (0–20 ppm) nitrate. Weekly 25–30% water changes will help refresh the system and keep everyone happy.

Chemistry is not critical and, provided the water is kept clean and fresh, temperatures between 22-28°C (72-82°F) and a neutral to slightly acidic pH and soft water will make them feel at home.

Otocinclus naturally occur in large shoals and are quite sociable, so if you want to try them go for at least six — or more if you have the space and algal growth.

Healthy fish will be very active during the day and diligently crop soft algae, diatoms and aufwuchs from any submerged surfaces in your aquarium.

Provide some pre-soaked branches or bogwood, rounded stones and vigorous aquatic plants.

Their small teeth are not really capable of breaking through tough plant tissues, so if they exhaust their supply of fresh algae they will need to be fed on something else. The stomachs of preserved, wild-caught specimens are typically filled with algae and fine organic matter.

I’ve found that Otocinclus in captivity will have a go at most prepared and frozen foods. They enjoy tablets, algae wafers, blanched spinach and courgette.

Safety – even in the shallows

I’ve collected Otocinclus in the Rio Itaya, Amazon drainage in Peru and Rio Apure and Portuguesa, Orinoco drainage in Venezuela, but they were never abundant.

We do not specifically target them, but they show up from time to time when we’re sampling submerged vegetation in flowing water. They can also be found attached to branches where they become snagged, for example, in the crook of a fallen-in tree.

Most emphasise these fishes’ preferences for aquatic and emergent plants along the shoreline. These are the most accessible and easily sampled aquatic habitats in large streams, so I don’t know if they are also in deepwater habitats.

That said, given their preferrence for algae and their built-in floatation aids — the esophageal gas bladder — I would not expect them below 50cm/20”. In the shallows they also avoid predation from other fishes and by hiding in vegetation avoid birds.

Ancistrus occupy shallows, where algal growth is highest, as juveniles and as they grow they move deeper to avoid kingfishers and herons, but enter the dangerous realm of Hoplias and Pseudopimelodus.

A preference for marginal habitats might also explain the large distribution of, for example, Otocinclus vittatus. At the streams’ edge, flow rate decreases and cataracts and rapids then become navigable if you are small enough to access the shallow margins.

Otocinclus are small catfishes, reaching 6-7cm/2.4-2.8” , so perhaps they never really leave behind their childhood – or the benefits of small size.

Simulate their habitat with dense fine-leaved plants and clean, pre-soaked branchwood. A sandy substrate keeps faeces on the surface until they can be drawn to the filter and provides a good rooting medium for the plants.

A mature filter with moderate to high turnover will keep water clean and well oxygenated and tank mates should include slow cichlids, peaceful characins, pencilfish and Corydoras.

Copycats

In South America, Otocinclus are usually found in low diversity streams in which characins such as Astyanax cruise the open water and Crenicichla lurk in the shadows. Four of the southern species are often found among or near to similarly patterned corydoradine catfishes, and several scientists suspect they are involved in mimetic relationships.

Otocinclus affinis is paired with Corydoras nattereri and Scleromystax prionotus, (O. flexilis) with C. paleatus, O. mimulus with C. diphyes and O. xakriaba with juvenile C. garbei.

By having similar body patterns to a distasteful or poisonous model means the mimic is less vulnerable to predation. In this case the predator learns to avoid the model (Corydoras) because they have sharp fin spines tipped with a toxin. The mimic (Otocinclus) copies that pattern to fool the predator into thinking that it is also a pretty painful proposition.

Similarities

If looking to add more authenticity to your aquarium biotope then add one of these mimetic pairs and watch how they interact, if at all, when a potential predator lurks.

Similarities to Corydoras are more than skin deep. Otocinclus are spawned in captivity and several accounts typically describe how multiple males chase females and eventually embrace.

The female lays one or two eggs in a pelvic fin basket and places them individually on leaves, branches, glass panes, filter intake pipes and provides no further care – just like Corydoras.

Spawning usually takes place after a water change and the fry will take newly-hatched brineshrimp and blanched spinach. Any resulting fry will stand a good chance of survival in a planted aquarium or one dedicated to a shoal of Otocinclus, but otherwise they will likely become tasty titbits for Apistogramma.

Otocinclus are sexually dimorphic and females are larger and broad when their ovaries are ripe.

Males have a genital papilla and a patch of modified skin teeth (odontodes). This patch is on the lower half of the caudal peduncle, where the body meets the tail, and swirls in characteristic fashion.

The function of the patch has yet to be confirmed, but some specialists believe it may be involved in adhering or positioning the male during the spawning embrace when he curls his body around a female’s head.

Slime suckers

Some aquarists have reported seeing Otocinclus feeding on the skin mucus of other fishes, yet I’ve kept several species and never witnessed this parasitic behaviour. It could happen, if the host was in poor health and the Otocinclus was particularly hungry, but I don’t think it’s something to worry about in a healthy, well-fed aquarium.

So, if you like plants but not algae, have a lightly stocked and well-filtered aquarium, and appreciate a bargain, you could do a lot worse than a shoal of Otocinclus.

copyright © George Farmer

Buy with caution

Otocinclus do not receive the care they deserve on their journey to your local shop, and tens of thousands die shortly after arrival.

I’ve been unable to find a solid explanation why they do, but suspect that their size, price and natural abundance mean they are held and shipped in high and stressful numbers.

Keeping Otocinclus in such densities, even temporarily, likely creates a pollution problem that doesn’t kill these small fishes outright but does lasting damage to delicate tissues such as the gills and liver. This means that secondary bacterial infections are more likely and without the appropriate treatment they will quickly succumb.

Even with correct diagnosis of the pathogen and a vet’s help it is very difficult to treat these small animals successfully.

So resist the urge to impulse buy! Talk to your shop owner or manager about history and losses among these fishes. If they have been in stock for at least two weeks and losses are less than 25%, select six to ten actively browsing aquarium surfaces, are brightly coloured and have their fins held out.

Quarantine them for two weeks, if you have the facilities, to ensure they are clean. Medicated flake foods and proprietary fluke treatments can give extra peace of mind.

The ideal Otocinclus set-up is a planted tank and the lucky few bought by aquarium gardeners are living in their own Shangri-La. For those keeping fish rather than plants, Otocinclus do well in Amazonian biotope aquaria populated by slow-moving cichlids such as angelfish and Discus.

While other fishes ignore them, any large predator will treat them as a snack.

If you enjoyed this article, why not take out a subscription to Practical Fishkeeping magazine? See our latest subscription offer.